The Renaissance of Electric Vehicles

Public Summary

Introduction

As awareness of climate change and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions increases, people turn to solutions such as ‘clean’ electric vehicles (EVs) produced by Tesla. These vehicles are increasingly in demand as they do not cause tailpipe emissions making them seem favorable toward addressing our changing climate (Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021). This growing demand has caused EVs to be more accessible and cheaper than ever before. It is important to look closely at this growing technology to investigate what is actually occurring through each stage of the development and use of EVs and how it is affecting the environment in comparison to traditional Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles (ICEVs) (Jones, Elliott and Nguyen-Tien, 2020). Essentially, are EVs actually helping the environment as much as they say they are? Or are they being marketed this way to increase sales?

Areas of Environmental Concern

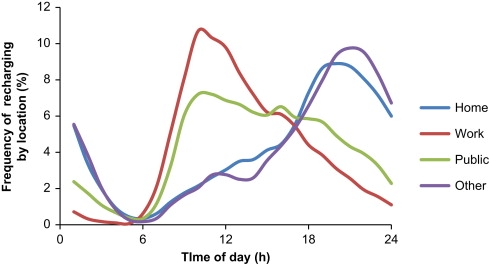

The process of a vehicle’s life cycle, from raw materials to the recycling of leftover parts has various consequences. Through the extraction of materials for EVs there are several environmental impacts. Primarily the extraction and refining of rare earth metals and minerals. The mining of minerals is associated with significant freshwater eutrophication, human toxicity, and depletion of metals. This is mainly as a result of the concentration of many EV minerals within a few select countries, many of which have questionable human rights and environmental policies, such as China and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Kang, Chen and Ogunseitan, 2013). Moreover, although EVs have 20-27% lower Life Cycle Impact than ICEVs (Elligsen et al., 2016), they do require six times the mineral output (IEA, 2021). The process of assembling EVs from materials generally produces higher emissions of GHGs and other harmful pollutants than the manufacturing of a traditional ICEV (Velandia Vargas et al., 2019). The higher emissions of EVs are caused by the production of electric battery packs and other electrical elements. However, the extent of the difference between these vehicles’ emissions is dependent on the region in which parts are produced due to importation emissions and regional environmental laws (European Environment Agency, 2018). Moreover, concerns have been raised about power grid integration and recharging EVs at times that coincide directly with pre-existing peaks in electricity consumption, thereby creating a “peak on peak” effect (Figure 1) (Kapustin and Grushevenko, 2020). This may overpower the grid and cause deterioration of the power quality, transmission line damage, and higher fault current (Rizvi et al., 2018). Many solutions to this issue have been proposed and implemented, such as battery swapping and vehicle to grid theory (Zhao and Baker, 2022).

Figure 1: EV recharging profiles throughout the day at the household, the workplace, in public, and other locations. Peak charging times for the workplace and public are hours 6-12 during the day. Peak charging times for home and other locations are hours 18-24 during the day. These times coincide with pre–existing peaks in energy demand (Robinson, 2013).

Conclusion

It is important to note that EVs impacts can greatly vary in different countries due to factors such as reliance on personal vehicles, location of important resources, and the energy sources used for the power grid (European Environment Agency, 2018). Ultimately, this investigation found that EVs can reduce environmental impacts when compared to ICEVs as they do not emit as much when in use (Elligsen et al., 2016). However, EVs’ still have damaging effects on the environment and are not a “silver bullet” for climate change.

References

Ellingsen, L.A.-W., Singh, B. and Strømman, A.H., 2016. The size and range effect: lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions of electric vehicles. Environmental Research Letters, 11(5), p.054010. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/5/054010.

European Environment Agency, 2018. Electric vehicles from life cycle and circular economy perspectives: TERM 2018 : Transport and Environment Reporting Mechanism (TERM) report. [online] LU: Publications Office. Available at: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2800/77428 [Accessed 14 November 2022].

IEA, 2021. The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions. [online] Paris. Available at: https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions/executive-summary [Accessed 4 November 2022].

Jones, B., Elliott, R.J.R. and Nguyen-Tien, V., 2020. The EV revolution: The road ahead for critical raw materials demand. Applied Energy, 280, p.115072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.115072.

Kang, D.H.P., Chen, M. and Ogunseitan, O.A., 2013. Potential Environmental and Human Health Impacts of Rechargeable Lithium Batteries in Electronic Waste. Environmental science & technology, 47(10), pp.5495–5503. https://doi.org/10.1021/es400614y.

Kapustin, N.O. and Grushevenko, D.A., 2020. Long-term electric vehicles outlook and their potential impact on electric grid. Energy Policy, 137, p.111103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111103.

Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J.B.R., Maycock, T.K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, Ö., Yu, R. and Zhou, B. eds., 2021. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press. DOI: 10.1017/9781009157896.

Rizvi, S.A.A., Xin, A., Masood, A., Iqbal, S., Jan, M.U. and Rehman, H., 2018. Electric Vehicles and their Impacts on Integration into Power Grid: A Review. 2018 2nd IEEE Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), pp.1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/EI2.2018.8582069.

Robinson, A.P., Blythe, P.T., Bell, M.C., Hübner, Y. and Hill, G.A., 2013. Analysis of electric vehicle driver recharging demand profiles and subsequent impacts on the carbon content of electric vehicle trips. Energy Policy, 61, pp.337–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.05.074.

Velandia Vargas, J.E., Falco, D.G., da Silva Walter, A.C., Cavaliero, C.K.N. and Seabra, J.E.A., 2019. Life cycle assessment of electric vehicles and buses in Brazil: effects of local manufacturing, mass reduction, and energy consumption evolution. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 24(10), pp.1878–1897. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-019-01615-9.

Zhao, G. and Baker, J., 2022. Effects on environmental impacts of introducing electric vehicle batteries as storage - A case study of the United Kingdom. Energy Strategy Reviews, 40, p.100819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2022.100819.