A Hot Topic: Climate Change and Epidemiology (Executive Summary)

Investigating the disease dynamics of cholera, malaria, and influenza in response to climatic variation

Christina Brinza, Grace Burgess, Sydney Deslippe, Michelle Kooleshova, Will Roderick

Climate influences many natural systems. One potentially devastating consequence of a changing climate is a shift in the range and evolution of human diseases caused by changes in temperature and precipitation. So how can we predict and understand the evolution of disease? To accomplish this, we examine how three diseases—cholera, malaria, and influenza—are predicted to respond to climate change.

Cholera is a human illness caused by a bacterium called Vibrio cholerae, which is naturally present in bodies of water around the world, and is responsible for many deaths in low-income countries (Constantin de Magny and Colwell, 2009). Its transmission is affected by regional temperature and precipitation. Higher temperatures lead to greater proliferation of cholera bacteria, while precipitation affects their aquatic habitat (Paz, 2009). Three separate studies demonstrated that changes in rainfall are strongly correlated with increases in cholera occurrence, indicating that changes in precipitation patterns associated with climate change may increase cholera incidence (Eisenberg et al., 2013; Lemaitre et al., 2019; Hashizume et al., 2008).

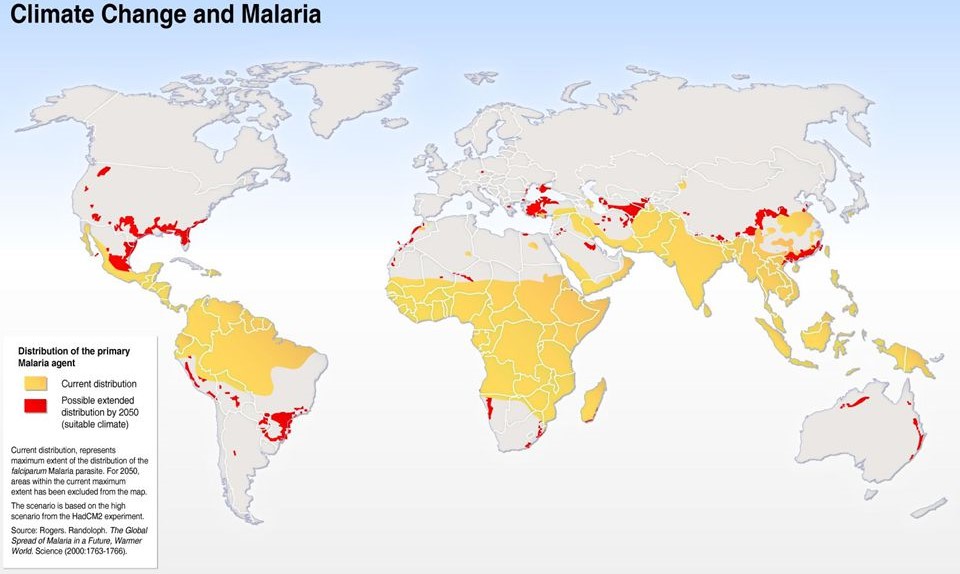

Figure 1: A map of the current areas of malaria distribution (in yellow), and the possible expansion of these areas due to climate change by 2050, based on a model by the Hadley Centre (in red) (Rogers and Randolph, 2000; de Souza, Owusu and Wilson, 2012).

Another interesting case study is malaria. This parasitic disease is caused by an organism in the genus Plasmodium, which is transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected female mosquito (Rogers and Randolph, 2000). Both the malaria parasite and its vectors are sensitive to temperature, precipitation, and humidity. Thus, climate has the potential to greatly influence the spatial limits and seasonal activity of malaria distribution (Caminade et al., 2014). However, additional confounding variables and gaps in existing models, such as the one shown in Figure 1, make the future distribution of malaria difficult to predict (Yacoub, Kotit and Yacoub, 2011). It is likely that despite susceptibility to climate change, the increase in preventative measures and other factors will result in a similar or lower prevalence of malaria in the future.

Lastly, influenza is a viral respiratory disease affecting approximately one billion people per year (WHO, 2018). The virus is present in the population year-round, but disease incidence is much higher during the winter, when North America experiences a “flu season” (Fisman, 2012). Different variants of influenza are likely to respond in different ways to climate change (Zhang et al., 2020), but in temperate regions, the increase in the number of mild winters could lead to more severe flu seasons (Towers et al., 2013).

These analyses are limited by the presence of confounding variables and the limited applicability to determining the cumulative effect of climate change on the epidemiology of other diseases. Also, the effects of climate change on other aspects of public health are intimately associated with disease epidemiology. For example, a decrease in food availability as a result of climate change could result in malnutrition and mental health risks, which, from a healthcare standpoint, could mean an increase in deficiency diseases and decrease in patient resiliency (Mirsaeidi et al., 2016). Establishing surveillance and response programs capable of eliciting effective and rapid response from healthcare institutions may help to mitigate increasing rates of incidence of cholera and influenza. In summary, climate change will impact the seasonality and range of cholera, malaria, and influenza, as well as other diseases, posing a direct and indirect risk to human health and established health care systems.

Works Cited

Caminade, C., Kovats, S., Rocklov, J., Tompkins, A.M., Morse, A.P., Colón-González, F.J., Stenlund, H., Martens, P. and Lloyd, S.J., 2014. Impact of climate change on global malaria distribution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(9), pp.3286–3291. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1302089111.

Constantin de Magny, G. and Colwell, R.R., 2009. Cholera and Climate: A Demonstrated Relationship. *Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association, 120, pp.119–128.

Eisenberg, M.C., Kujbida, G., Tuite, A.R., Fisman, D.N. and Tien, J.H., 2013. Examining rainfall and cholera dynamics in Haiti using statistical and dynamic modeling approaches. Epidemics, 5(4), pp.197–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epidem.2013.09.004.

Fisman, D., 2012. Seasonality of viral infections: mechanisms and unknowns. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 18(10), pp.946–954. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03968.x.

Hashizume, M., Armstrong, B., Hajat, S., Wagatsuma, Y., Faruque, A.S.G., Hayashi, T. and Sack, D.A., 2008. The Effect of Rainfall on the Incidence of Cholera in Bangladesh. Epidemiology, 19(1), pp.103–110. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e31815c09ea.

Lemaitre, J., Pasetto, D., Perez-Saez, J., Sciarra, C., Wamala, J.F. and Rinaldo, A., 2019. Rainfall as a driver of epidemic cholera: Comparative model assessments of the effect of intra-seasonal precipitation events. Acta Tropica, 190, pp.235–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.11.013.

Mirsaeidi, M., Motahari, H., Taghizadeh Khamesi, M., Sharifi, A., Campos, M. and Schraufnagel, D.E., 2016. Climate Change and Respiratory Infections. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 13(8), pp.1223–1230. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201511-729PS.

Paz, S., 2009. Impact of Temperature Variability on Cholera Incidence in Southeastern Africa, 1971–2006. EcoHealth, 6(3), pp.340–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-009-0264-7.

Rogers, D.J. and Randolph, S.E., 2000. The global spread of malaria in a future, warmer world. Science (New York, N.Y.), 289(5485), pp.1763–1766.

de Souza, D., Owusu, P. and Wilson, M., 2012. Impact of Climate Change on the Geographic Scope of Diseases. pp.245–264. https://doi.org/10.5772/50646.

Towers, S., Chowell, G., Hameed, R., Jastrebski, M., Khan, M., Meeks, J., Mubayi, A. and Harris, G., 2013. Climate change and influenza: the likelihood of early and severe influenza seasons following warmer than average winters. PLoS Currents. [online]

WHO, 2018. Influenza (Seasonal). [online] Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal) [Accessed 7 Mar. 2021].

Yacoub, S., Kotit, S. and Yacoub, M.H., 2011. Disease appearance and evolution against a background of climate change and reduced resources. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 369(1942), pp.1719–1729. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2011.0013.

Zhang, Y., Ye, C., Yu, J., Zhu, W., Wang, Y., Li, Z., Xu, Z., Cheng, J., Wang, N., Hao, L. and Hu, W., 2020. The complex associations of climate variability with seasonal influenza A and B virus transmission in subtropical Shanghai, China. Science of The Total Environment, 701, p.134607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134607.