The Ethics of Geoengineering

Grace Horseman, Helen MacDougall-Shackleton, Max Rival, Jessica Wassens

Introduction

Geoengineering is the “deliberate large-scale manipulation of the planetary environment to counteract anthropogenic climate change” (The Royal Society, 2009, p.1), and its discussion has become increasingly mainstream in recent years (IPCC, 2015). Although these technologies are still largely speculative, the social, legal, and political issues presented by geoengineering are already hotly debated — these arguments are discussed below in order to explore the question “is geoengineering ethical?”

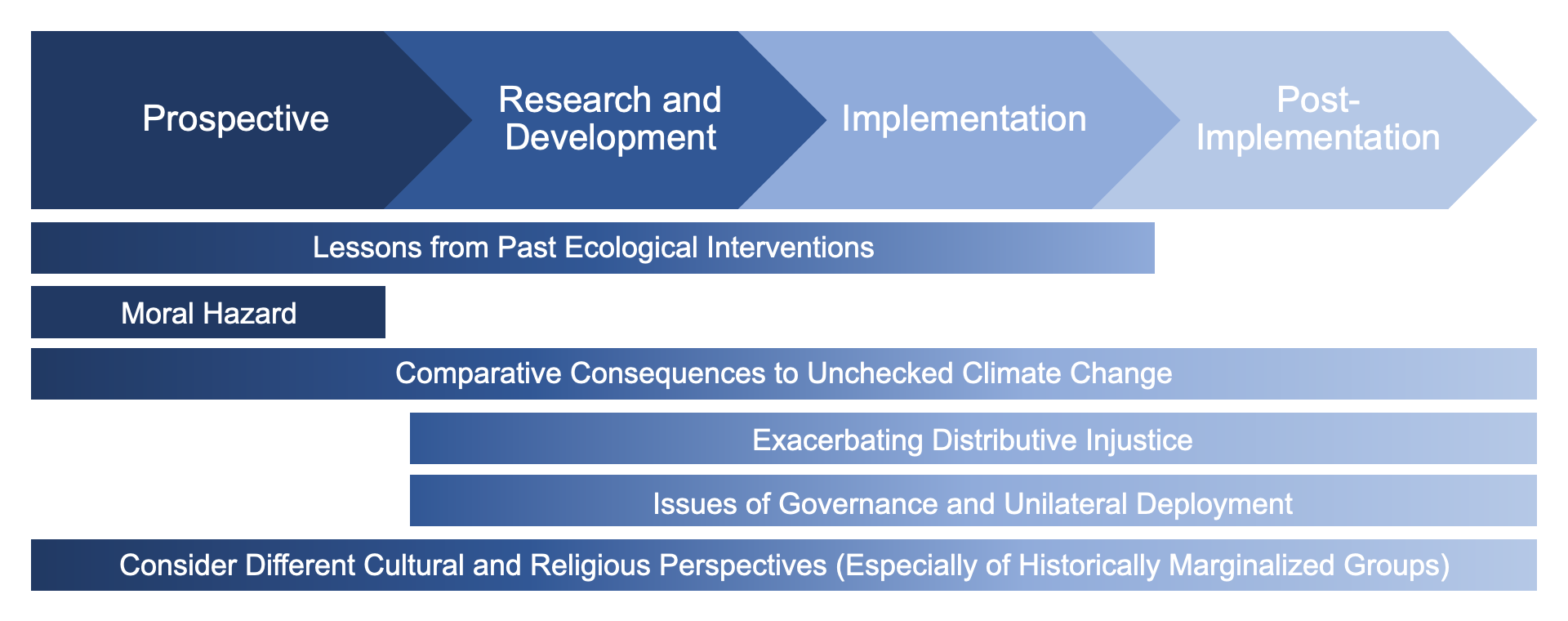

Figure 1. Geoengineering presents ethical challenges at every stage, from contemplating it as a prospect to planning for its cessation. Here, important issues to consider at the Prospective, Research and Development, Implementation, and Post-Implementation stages are represented graphically. The colours of the bars represent the stages at which each issue is most relevant.

Figure 1. Geoengineering presents ethical challenges at every stage, from contemplating it as a prospect to planning for its cessation. Here, important issues to consider at the Prospective, Research and Development, Implementation, and Post-Implementation stages are represented graphically. The colours of the bars represent the stages at which each issue is most relevant.

Historical Ecological Interventions as Geoengineering Analogues

There is a long history of deliberate human interventions in environmental systems, often with unpredictable responses (e.g., failed biocontrol of invasive species) (Matthews and Turner, 2009). Past failures have often been caused by a limited understanding of complex systems, and a tendency to learn from past mistakes through trial-and-error. Looking to these examples as analogues for geoengineering, we can conclude that it is too risky and uncertain to pursue as a response to climate change, given our limited understanding of the climate system.

Moral Hazard Arguments

One common and historically important argument against geoengineering is that it presents a ‘moral hazard’, meaning that implementing, researching, or even discussing geoengineering could undermine efforts to mitigate or adapt to climate change. By seemingly providing ‘insurance’ against climate change, geoengineering technologies may act as disincentives for or diversions from other solutions, or even lead to higher emissions (The Royal Society, 2009). Although it is difficult to directly assess this risk, studies of moral hazard in other contexts and well-accepted frameworks for human behaviour suggest this concern is warranted (Lin, 2013).

Consequences of Geoengineering Compared to Global Warming

Global warming severely threatens human life on Earth, through rising sea levels and increased natural disaster frequency, in addition to other global issues (IPCC, 2015). Geoengineering, which could halt warming (IPCC, 2018), has seemingly less severe consequences, such as ozone depletion (Robock, 2008; Robock et al., 2009; Liu and Chen, 2015). However, due to general uncertainties, as well as the inability for certain techniques to address rising CO2 levels (Liu and Chen, 2015), geoengineering in its current form cannot be justified.

Distributive Justice

Rural, poor, and vulnerable populations, such as those that rely on subsistence farming and Indigenous nations, will disproportionately bear the environmental and economic consequences of geoengineering research and deployment (Schneider, 2019). Among these consequences are worsening food insecurity (Robock, Oman and Stenchikov, 2008; McLaren, 2018), risks of disease (Carlson et al. 2020), and income inequality (Harding et al., 2020). These concerns for justice also extend to future generations, especially in a scenario where geoengineering is suddenly stopped (Svoboda et al., 2011).

Politics and the Risk of Unilateral Deployment

Due to geoengineering’s global influence, the people in control must be carefully chosen (Gardiner and Fragnière, 2018). Existing global frameworks for climate governance should be used to establish a unified approach (Virgoe, 2009). However, geoengineering remains a political uncertainty, as climate goals of different nations may not align (Virgoe, 2009; Corry, 2017). Furthermore, the inexpensiveness of certain technologies runs the risk of unilateral deployment, further jeopardizing political support (Victor, 2008; Bodansky, 2013).

Religious and Cultural Perspectives

Current approaches to geoengineering ethics are rooted in Western ideas and morals (Horton, 2017; Sikka, 2020). However, diverse cultural, historical, and religious understandings of human-human, human-nature, and human-technology relationships exist globally. While the diversity of cultural and religious traditions are important to consider for geoengineering to be inclusive, different perspectives on these relationships can make valuable contributions to the way geoengineering is framed and approached (Clingerman and O’Brien, 2014; Sugiyama et al., 2017).

Conclusion

When considering deliberate climate intervention, it is critical to first consider the ethical implications of geoengineering research, testing, and deployment. In general, the arguments we explore suggest that geoengineering is not an ethical solution for climate change, and that policy-makers should instead consider alternative measures.

References

Bodansky, D., 2013. The who, what, and wherefore of geoengineering governance. Climatic Change, 121(3), pp.539–551.

Carlson, C.J., Colwell, R., Hossain, M.S., Rahman, M.M., Robock, A., Ryan, S.J., Alam, M.S. and Trisos, C.H., 2020. Solar geoengineering could redistribute malaria risk in developing countries. medRxiv.

Clingerman, F. and O’Brien, K.J., 2014. Playing God: Why religion belongs in the climate engineering debate. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 70(3), pp.27–37.

Corry, O., 2017. The international politics of geoengineering: The feasibility of Plan B for tackling climate change. Security Dialogue, 48(4), pp.297–315.

Gardiner, S.M. and Fragnière, A., 2018. Geoengineering, Political Legitimacy and Justice. Ethics, Policy & Environment, 21(3), pp.265–269.

Harding, A.R., Ricke, K., Heyen, D., MacMartin, D.G. and Moreno-Cruz, J., 2020. Climate econometric models indicate solar geoengineering would reduce inter-country income inequality. Nature Communications, 11(1).

Horton, Z., 2017. Going Rogue or Becoming Salmon? Geoengineering Narratives in Haida Gwaii. Cultural Critique, 97, pp.128–166.

IPCC, 2015. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. [online] Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC.p.151. Available at: https://ar5-syr.ipcc.ch/ipcc/ipcc/resources/pdf/IPCC_SynthesisReport.pdf [Accessed 3 Mar. 2021].

IPCC, 2018: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. [Core Writing Team, Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I., Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)]. [online] Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC.p.350. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/06/SR15_Full_Report_Low_Res.pdf [Accessed 3 Mar 2021].

Lin, A.C., 2013. Does Geoengineering Present a Moral Hazard? Ecology Law Quarterly, 40(3), pp.673–712.

Liu, Z. and Chen, Y., 2015. Impacts, risks, and governance of climate engineering. Advances in Climate Change Research, 6(3), pp.197–201.

Matthews, H.D. and Turner, S.E., 2009. Of mongooses and mitigation: ecological analogues to geoengineering. Environmental Research Letters, 4(4), p.045105.

McLaren, D.P., 2018. Whose climate and whose ethics? Conceptions of justice in solar geoengineering modelling. Energy Research & Social Science, 44, pp.209–221.

Robock, A., 2008. 20 Reasons Why Geoengineering May Be a Bad Idea. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 64(2), pp.14–18.

Robock, A., Oman, L. and Stenchikov, G.L., 2008. Regional climate responses to geoengineering with tropical and Arctic SO2 injections. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 113(D16).

Robock, A., Marquardt, A., Kravitz, B. and Stenchikov, G., 2009. Benefits, risks, and costs of stratospheric geoengineering. Geophysical Research Letters, 36(19).

Schneider, L., 2019. Fixing the Climate? How Geoengineering Threatens to Undermine the SDGs and Climate Justice. Development, 62(1), pp.29–36.

Sikka, T., 2020. Activism and Neoliberalism: Two Sides of Geoengineering Discourse. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 31(1), pp.84–102.

Sugiyama, M., Asayama, S., Ishii, A., Kosugi, T., Moore, J.C., Lin, J., Lefale, P.F., Burns, W., Fujiwara, M., Ghosh, A., Horton, J., Kurosawa, A., Parker, A., Thompson, M., Wong, P.-H. and Xia, L., 2017. The Asia-Pacific’s role in the emerging solar geoengineering debate. Climatic Change, 143(1), pp.1–12.

Svoboda, T., Keller, K., Goes, M. and Tuana, N., 2011. Sulfate aerosol geoengineering: the question of justice. Public Affairs Quarterly, 25(3), pp.157–179.

The Royal Society, 2009. Geoengineering the Climate: Science, Governance and Uncertainty. [online] Available at: https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/156647/1/Geoengineering_the_climate.pdf.

Victor, D.G., 2008. On the regulation of geoengineering. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 24(2), pp.322–336.

Virgoe, J., 2009. International governance of a possible geoengineering intervention to combat climate change. Climatic Change, 95(1), pp.103–119.