Lesson 1: Learn MATLAB

Estimated time to complete: 45-60 minutes

In this lesson, you’ll become familiar with the MATLAB interface, and learn the basic syntax of programming in MATLAB.

Video (Part 1)

1. The MATLAB interface

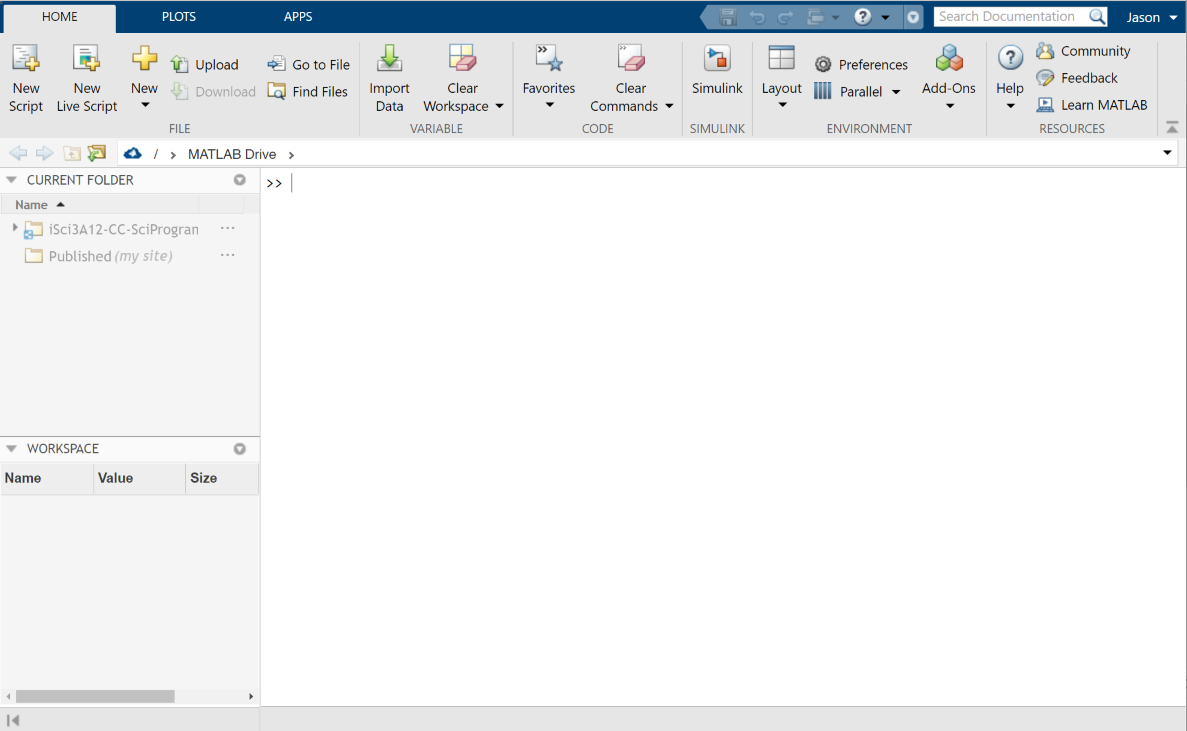

By default, the MATLAB Online interface consists of following panels:

By default, the MATLAB Online interface consists of following panels:

- The tool panels at the top (which include

HOME,PLOTS, andAPPStabs. - The path selector, which will be set initially to

/ > MATLAB DRIVE. This indicates the directory where MATLAB is currently set to operate. - The CURRENT FOLDER browser, which will show the files and folders in your MATLAB Drive.

- The WORKSPACE, which allows you to view/edit data (variables) that you’ve imported or created.

- The COMMAND WINDOW, which allows you to enter commands to MATLAB (after the

>>prompt).

2. Numeric variables

2.1. Assigning and naming variables

- Into Command Window, enter a single digit, such as

8. Notice how MATLAB assigns the inputted value to a variable calledans. MATLAB stores all values that are given to it as variables.ansis the default name given to a variable if a name is not specified. - Now enter another digit into the Command Window, like

7. Notice thatans=8is now overwritten byans=7. - To avoid overwritting variables and to make more useful variable names, you can assign names and values to variables:

a = 8 b = 7 test123 = 12 c = a; - In your Workspace, you’ll see that you have

a,b,candtest123listed. You can view the value of a variable by typing the variable name back into the command window:test123 - You may have also noticed that MATLAB has echoed your commands in the Command Window. Use a semicolon at the end of a command to avoid the echo:

test123 = 14;

2.2. Removing a variable from the workspace

- You can remove a variable from your workspace by using the

clearfunction.- e.g.

clear cwill remove the variablec.

- e.g.

- You can remove all variables in the Workspace with the

clearvarscommand.- e.g.

clearvarswill remove all variables (but don’t do this right now).

- e.g.

- You can clear the contents of the Command Window at any time by typing

clc.

Video (Part 2)

2.3. Scalars, Vectors and Matrices

All previous variables you’ve created to this point are scalars (i.e. 1 row x 1 column). You can use brackets ([ and ]) to create vectors and matrices.

- e.g. Create a 1x5 row vector (i.e. 1 row and 5 columns) by placing spaces between values:

rv1 = [2 19 3 -3 4] - e.g. Create a 5x1 column vector (i.e. 5 rows and 1 column) by using the semicolon (;) to start a new row:

cv1 = [31; 8; -10; 39; 2] - An apostrophe after the vector/matrix transposes it. e.g. Transpose a row vector into a column vector by adding

':cv2 = [31 a -10 39 2]' - Matrices can be created by expanding the examples above into multiple rows and columns.

- e.g. Create a 5x4 (5 rows x 4 columns) matrix called

mymatrix1:mymatrix1 = [12 4 2 1; 13 4 1 23; 39 20 10 9; 3 -22 -12 0; 78 -6 -3 2];

- e.g. Create a 5x4 (5 rows x 4 columns) matrix called

2.4. Not a Numbers (NaN)

Occasionally, matrices can have missing values. In such cases, you can use the notation NaN to indicate that there is a missing value in an element of a matrix. This is important when the location of values in a matrix are important (e.g. a time series collected at regular intervals). Note: The value NaN is a special character recognized by MATLAB as a null value. Any normal operations that are carried out on variables containing NaNs will result in NaN.

- e.g. Create a matrix with a couple of

NaNvalues:cv3 = [4 NaN 5; 9 10 NaN; 8 10 4];

2.5. Referencing elements in vectors, matrices

You can reference specific elements in a vector/matrix using parentheses (( and )). NOTE that locations are specified by (row# , column#), and you can use the colon (:) operator to specify an entire row or column.

- e.g. Assign variable

dthe value of the element in row3, column3 ofmymatrix1d = mymatrix1(3,3); - e.g. Assign variable

ethe value of entire first column ofmymatrix1e = mymatrix1(:,1);

2.6. Exercise

- Create a 6x2 matrix, name it

mymatrix2. - Create a new variable called

mycolumn, which consists of the second column of mymatrix2.

3. Operations (arithmetic, trigonometric, statistical)

3.1. Arithmetic operations

- Common arithmetic operations use the expected operations, e.g.:

23+7 % Add: a-b % Subtract 23*a % Multiply 23/b % Divide d = 8^2.5 % Exponent sqrt(a+b) % square root: - Arithmetic operations can also be used on vectors and matrices, e.g.:

cv1 - 8 % subtract 8 from each element cv1 / 8 % divide each element by 8 sqrt(mymatrix1) % notice the imaginary parts where mymatrix1 values are negative - You can add or subtract two vectors element-wise (like subtracting values in one column in Excel from another) using arithmetic operations, e.g.:

cv1-cv2 % subtract elements of cv2 from cv1- NOTE that element-wise addition or subtraction will only work if both vectors/matrices are the same size–otherwise, you’ll get an unexpected result or an error. For example,

cv1-rv1will give you a 5x5 matrix result, where cv1 and rv1 are replicated to 5x5 matrices and then subtracted from each other element-wise.

- NOTE that element-wise addition or subtraction will only work if both vectors/matrices are the same size–otherwise, you’ll get an unexpected result or an error. For example,

- For multiplication and division, placing a period in front of the operator specifies an element-wise operation, e.g;

cv3 = cv1.*cv2; % element-wise multiplication cv4 = cv1./cv2; % element-wise division- NOTE that performing these operations without periods before the operators will do something different. e.g:

rv1*cv1will perform matrix multiplicationrv1/cv1will return an error, as it is attempting to solve a set of linear equations.

- NOTE that performing these operations without periods before the operators will do something different. e.g:

3.2. Logarithmic, trigonometric operations

See examples below:

log_d = log(d) % natural logarithm

log10_d = log10(d) % base10 logarithm

exp_cv1 = exp(cv1) % natural exponent

cos_m1 = cos(mymatrix1) % cosine function

sin_d = sin(d) % sine function

tan_d = tan(d) % tangent function

3.3. Statistical operations

See examples below:

mean_cv1 = mean(cv1) % mean

mode_cv1 = mode(cv1) % mode

std_m1 = std(mymatrix1) % standard deviation; notice it takes the standard deviation for each column

std_m1b = std(mymatrix1,0,2) % This will take stdev across rows, instead.

var_m1 = var(mymatrix1) % variance

4. Learning more about MATLAB

- There are two helpful commands for learning more about what a MATLAB function (like

mean, for example) does:- To view help documentation in the command window type

helpand the name of the function- e.g.

help mean;

- e.g.

- To view documentation in a separate window, type

docand the name of the function- e.g.

doc mean;

- e.g.

- To view help documentation in the command window type

5. Scripts

To this point, you have entered all of your operations into the command window. This is fine if you only have to perform a couple of operations a few times, but if you want to build a set of connected and repeatable commands, it’s best to create a script or function. (We’ll discuss functions later).

- In MATLAB, click the

New Scriptbutton to open a new script. Complete the rest of this lesson in the new script, but typing each command into a new line.- Tip1 You can execute all lines in a script (i.e. send them to the command window) at once by clicking the

Runbutton. - Tip2 You can execute a line (or set of lines) of code in a script by highlighting them and pressing the F9 key. This is very helpful!

- Tip1 You can execute all lines in a script (i.e. send them to the command window) at once by clicking the

6. Types of MATLAB arrays

To this point, we’ve worked entirely with numeric arrays. MATLAB provides for a number of other variable types to be used. Typically, the most appropriate variable type depends on the nature of your data and your desired processes and outcomes. Here are the MATLAB variable types:

- integer arrays (of varying length, signed/unsigned)

- numeric arrays (real numbers)

- logical arrays (values of 1 or 0, representing true and false)

- e.g.

f = [12 -3 NaN 7];list_nans = isnan(f)

- e.g.

- character arrays (strings stored as vectors of characters)

- e.g.

char1 = 'my first string';char2 = 'is not my last';

- e.g.

- cell arrays (array of indexed cells, each capable of storing an array of different dimension and type; think of Excel spreadsheets, if each cell could contain countless more cells inside of it)

- e.g.

cell1 = {345, 'Mazda', [34 43]; 34, NaN, 'zoom'}

- e.g.

- structure arrays (expandable tree of variables, which can each be of different size and type)

- e.g.

s.a = 1; s.b = {'A','B','C'};

- e.g.

- objects (user classes and java classes)

Below, you’ll learn a bit more about basic array types.

6.1. Numeric arrays

You’ve already had a basic introduction to numeric arrays through your work with scalars, vectors and matrices.

6.2. Character arrays

- Create two character arrays using strings of characters; assign them variable names. e.g.:

char1 = 'my first string' char2 = 'is not my last' - Combine (concatenate) the two character arrays into a new single character array. e.g.:

char3 = [char1 char2]; - Figure out how to insert another string between char1 and char2

6.3. Cell arrays

- Create a 2x2 cell array, where one of the cells contains:

- a scalar (i.e. a single numeric value). e.g.:

cell1{1,1} = 99; - a character array. e.g.:

cell1{1,2} = 'bottles of beer on the wall'; - a matrix. e.g.:

cell1{2,1} = [1 2 3; 4 5 6; 7 8 9]; - a NaN. e.g.:

cell1{2,2} = NaN;

- a scalar (i.e. a single numeric value). e.g.:

- Double click on your cell array in the Workspace to inspect it in the Viewer window

6.4. Structure arrays

- Enter the following into your script and execute it:

student(1).name = 'John'; student(1).age = 23; student(2).name = 'Sabrina'; student(2).age = 24; - Create a new type of category for both students named

gradeand give each student a value.

7. Running a script

- In the Command window, clear all variables from the workspace with the

clearvars;command - Run your script using the

Runbutton. Note that you will be required to save it. Give it a useful name (no spaces or dashes) and save it to the same directory as the rest of your work.

8. Functions

In MATLAB, find and open the following files:

- The script

iSci_Intermediate.m - The function

isleapyear.m

Both files contain similar content (commands and comments), but they work a bit differently. The script iSci_Intermediate is essentially a list of commands intended to run sequentially (by hitting the Run button or highlighting sections and executing with the F9 key).

Functions like isleapyear are similar to scripts in that they contain a set of commands to be executed. Where they differs, however, is that functions run with a separate workspace (called a stack). By default, the function does not have access to variables in the main MATLAB Workspace and variables in the function’s stack will not be accessible from the command line.

Instead, you pass data into and out of functions when you call them. The function declaration statement (at the top of the function) defines which variables will be passed into and out of it.

- For example, a function declaration looks something like:

function [output1,output2] = name_of_function(input1,input2,input3), where outputs are placed in brackets before the equals sign and expected inputs are listed after the function name. Functions can have any number of input and output variables, and can be named mostly anything (as long as they don’t have a special character or a space in them). Functions are useful when you are interested in only some output variables in a set of commands. You can also run a function inside of a script (or another function), which makes it a very space and time-saving way to run many commands.

Functions are called using their name and the output/input format specified above. For example, the operation mean is a function with the form [avg] = mean(input);, where avg is the output variable, mean is the function name, and input is the input variable or value.

When using a function in the Command Window or a script, you can choose the name of the output variable. The following two examples have the same output, but return the result in variables of different names:

x = mean([1 2 4 5 -10]);

avg_value = mean([1 2 4 5 -10]);

9. Comments

You’ll notice that the scripts and functions contain more than just the commands meant to be executed in MATLAB–there is additional information provided that explains the scripts/functions and the code found within. These are called comments. In MATLAB, the % character is used to indicate a comment–it appears in green in the editor, and anything on a line after the % character is ignored by MATLAB when the script/function is run. Comments are a very crucial part of coding, as it provides documentation for future users (including yourself) to figure out what you are doing at each point of a program and why. It is always good practice to comment a description of the program at its top, and comment thoroughly throughout the program. You can see an example of this in isleapyear.

10. Final Exercise

- Open

isleapyear.m.- Read the function declaration (very top line) and the introductory comments.

- What does this function do?

- What are the inputs and outputs?

- How can you use it?

- Who created it and when?

- Read the function declaration (very top line) and the introductory comments.

- Run

isleapyearfrom the command line a few times to check whether a few different years are leap years or not.

11. Proceed to the next lesson.

Phew. That was a lot. The good news is that you should now have a good sense of programming basics. Head to the next lesson to learn how to apply these basics to create scripts and functions that will carry out analyses.