The False Promise of Natural Gas Its Promotion Amid Detrimental Environmental Impacts

By Rishabh Bhatia, Brando Farruggia, Edward Hagerman, Diego Prieto, Jonah Wilbur

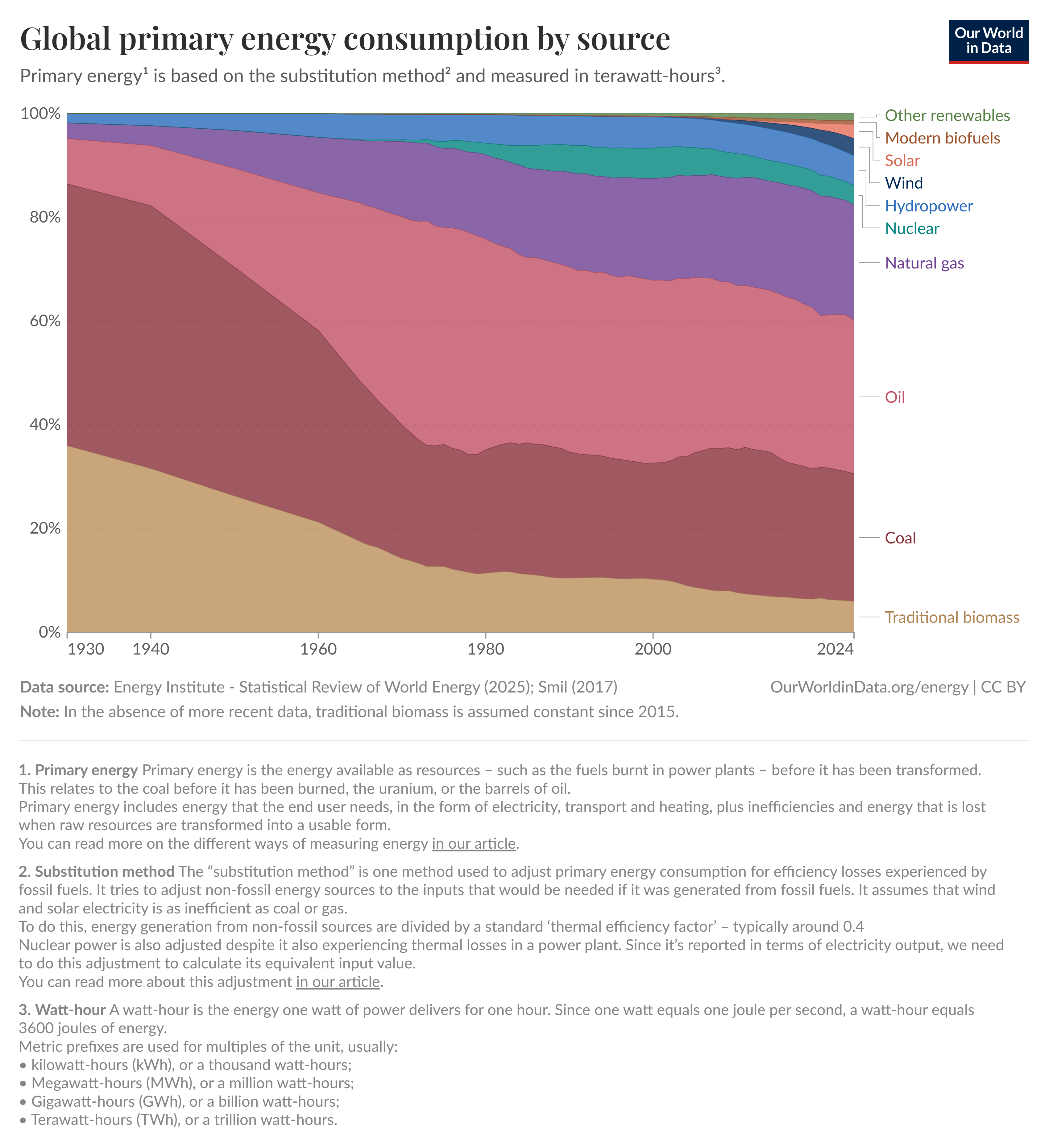

Over the past 50 years, natural gas (NG) has seen an explosion in popularity and usage. Natural gas was largely introduced as an alternative to coal after the Second World War and later oil following the oil crises of 1973 and 1979 (Cappelli et al. 2023). Its rapid expansion in the global energy share did initially bring about many positive changes which further incentivised governments and other actors to continually invest in the energy source. For instance NG dramatically reduced air pollution due to its lower particulate count when compared with coal and oil. One notable example being the reduction of particulate levels by over 60% in London, UK after the switch to NG (Power et al. 2023). These “miracles” led to its rapid expansion with NG standing at 22% of global energy supply in 2024 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Seen above is the change in the global energy mix as a percent in reference to all major fuel types. We can observe here the dramatic reduction in coal usage which has largely been supplanted by NG and oil. Today NG remains one of the world’s critical fuel sources and shows little sign of slowing.

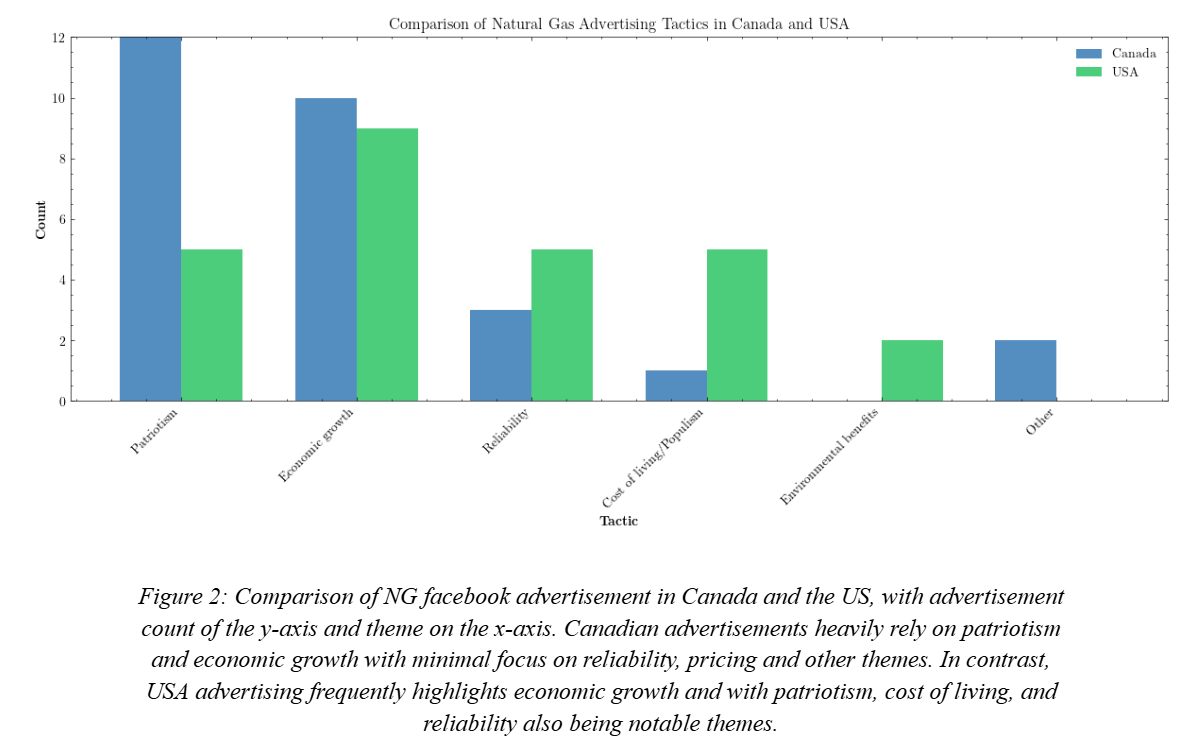

Advertising for NG helped to push this narrative and eventually NG was touted as the green solution to many of the world’s ills. In the wake of the environmentalist movements of the 1960s and 1970s, NG companies pushed hard for its place as a clean fuel. The NG lobby has always used marketing to help shift public perception of its industry. Today NG relies on drawing sympathy to a variety of claims, whether that be patriotism or economic concerns (Figure 2).

The constant push by these companies to inflate the importance, viability, and utility of NG to the nations of the world. While tactics differ from nation to nation the underlying goal remains the same, protect NG from true accountability and any significant regulation. As NG began to face mounting pressure for its role in climate change among other environmental concerns there was a shift in narrative. The bridge-fuel narrative emerged in 1988, pushing to present NG as a tool that could be used to “bridge” the transition into greater renewable usage (Ladd 2017). To help investigate these claims we examined three scenarios in which we (1) moved towards full renewables, (2) bridged our transition with NG and (3) did nothing. When examining the carbon dioxide released during each scenario from 2000-2050 we saw that while the bridge-fuel solution reduced emissions when compared with scenario 3 it still produced more than double those of a fully focused renewable transition.

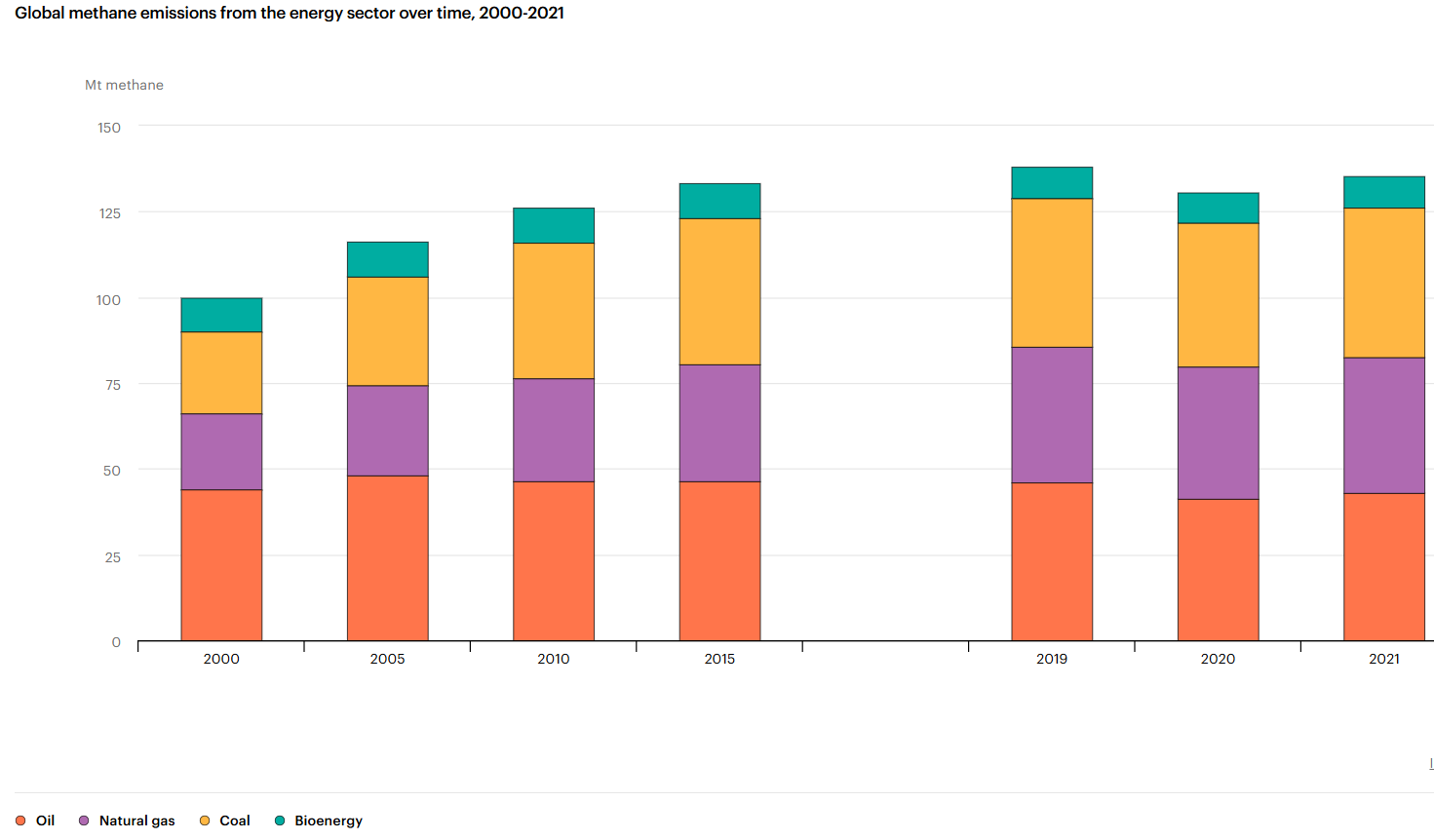

One of the greatest concerns we had is that carbon dioxide is not the only greenhouse gas.In fact, NG has an ugly secret that up until recently had remained little investigated. That secret is methane emissions. Methane, a simple and innocuous compound composed of just five atoms, one carbon and four hydrogen. Yet methane is responsible for over 30% of greenhouse gases and NG is an enormous contributor (Figure 3). Methane is an often overlooked aspect of climate change but it destroys any attempt to justify NG. Any offset in carbon dioxide is completely eviscerated and may even be overridden by the amount of methane released in the numerous pipelines without efficient tracking.

Figure 3: Above displays the methane emissions in millions of tonnes for various fossil fuel sources since 2000. We can see here the enormous role NG plays highlighted in purple. The role NG is playing in methane emissions not only continues to grow but many of these emissions are only now being document year over year due to previous failures in tracking. To date the full extent of NG’s methane emissions remains unclear and could be significantly larger (International Energy Agency 2022).

In summary, NG remains a serious threat to any attempt to handle the climate crisis. In order to help combat the dangers it poses it is critical to understand what the risks are and how industry continues to garner support both in government and among the public.

References

Cappelli, Federica, Giovanni Carnazza, and Pierluigi Vellucci. 2023. “Crude Oil, International Trade and Political Stability: Do Network Relations Matter?” Energy Policy 176 (May): 113479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113479.

International Energy Agency. 2022. “Methane and Climate Change – Global Methane Tracker 2022 – Analysis.” IEA. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-methane-tracker-2022/methane-and-climate-change.

Ladd, Anthony E. 2017. “Meet the New Boss, Same as the Old Boss: The Continuing Hegemony of Fossil Fuels and Hydraulic Fracking in the Third Carbon Era.” Humanity & Society 41 (1): 13–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160597616628908.

Power, Ann L., Richard K. Tennant, Alex G. Stewart, et al. 2023. “The Evolution of Atmospheric Particulate Matter in an Urban Landscape since the Industrial Revolution.” Scientific Reports 13 (1): 8964. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35679-3.

Ritchie, Hannah, and Pablo Rosado. 2020. “Energy Mix.” Our World in Data, July 10. https://ourworldindata.org/energy-mix.